Ingmar Bergman Ranked, Worst to Best

Ingmar Bergman. If you’ve heard of him, you probably either love him or hate him. Despite being widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers to ever live, I’ve found from experience that his films can be quite divisive upon first viewing. Though they’re almost invariably filled to the brim with thought-provoking imagery and meaningful dialogue, they can be slow, plodding, and even downright frustrating at times. I would know - this past month I watched (subjected myself to? endured?) 15 of Bergman’s most well-known films, including his two behemoth five-hour miniseries. That may seem like a lot, but given that Bergman directed over 60 feature length films throughout his career, 15 is really quite a small portion of the whole. Nevertheless, I hope that this brief ranking can provide a starting point for anyone hoping to get into one of the most intriguing directors of all time.

The Bad

15. Summer with Monika (1953)

If Summer with Monika is the worst movie you made, you’re really not doing too bad. That being said, Summer with Monika and The Magician are the only two Bergman films I actively dislike. Bergman’s greatest strength is his ability to quickly establish three-dimensional characters through believable dialogue. Unfortunately, that strength is almost entirely absent from this film. The two main characters, Monika (played by Bergman regular Harriet Andersson) and Harry (Lars Ekborg), come off as caricatures of young people looking for adventure and lack any notable qualities or motivations that make them stand out in a collection of movies with very similar themes. Ironically, Bergman would get better at writing young characters the older he became. Summer with Monika isn’t all bad, though - the cinematography is about as good as it gets, and the performances are solid all around. The issue really comes down to the lackluster writing and poor characterization. Skip Summer with Monika - there’s at least one better Bergman film with “Summer” in the title.

14. The Magician (1958)

The Magician is a really weird movie. It was made the year after Bergman released what are arguably his two most acclaimed films (The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries), and it almost seems like a response to criticisms that these movies were too severe and self-important. For better or worse (it’s definitely for worse), The Magician is not a serious film. It features Max von Sydow (Bergman’s poster child) in an absolutely ridiculous costume and wig as a struggling magician leading a troupe of similarly eccentric characters. The film is ostensibly about the tensions between religion and science, superstition and rationality, but there is very little to latch onto to draw any actual conclusions on those themes. The Magician is an interesting and light-hearted oddity in the Bergman catalog, but it’s not worth more than a cursory mention.

The Decent

13. Summer Interlude (1951)

Now this is what I’m talking about! One of his earliest outings, Summer Interlude contains all the hallmarks of a solid Bergman film. The writing is sharp, the lighting is stark, and the acting is as sleek as ever. Summer Interlude is a relatively light entry in the Bergman oeuvre, neglecting tales of religious trauma and grief in favor of nostalgia and lost love. It’s a fun, bittersweet tale and one I would absolutely recommend to anyone looking for an easy entry into Bergman’s filmography. My only major issue with the film is that it is entirely Bergman-by-the-numbers. The narrative is clean and straightforward with very little in the way of thematic proselytizing (which I admittedly love), and the cinematography takes little risks. Every shot is pleasing to the eye, but there are few that make an impression on the brain. Regardless, this is a pleasant diversion for a warm summer day.

12. The Silence (1963)

The Silence is one of Bergman’s most surreal films. Apart from a few scenes on the train, most of the movie takes place in an otherworldly hotel, not unlike The Shining’s Overlook Hotel. The characters, apart from the two leads played by Ingrid Thulin and Gunnel Lindblom, all feel like caricatures of other eccentric Bergman characters, lending the movie a narrative unpredictability that makes it simultaneously engaging and exhausting to sit through. Despite its tediousness, the film is an interesting meditation on communication and the disaster that ensues when there is a complete lack of understanding and empathy. The characters spend the entire movie talking past each other, speaking without saying anything. It makes for a film that is undoubtedly intriguing but often feels more like a provocative thought experiment than a full-fledged work of art.

11. Hour of the Wolf (1968)

Bergman’s only “straightforward” foray into horror, Hour of the Wolf is a frustrating film. I place “straightforward” in quotes, because though this is clearly a horror film, its narrative is characteristically convoluted and nightmarish. The issue with Hour of the Wolf is that it comes off as a series of memorable vignettes held together by a weak, pointless plot falsely justified by surrealism. Having seen the film just a few weeks ago at this point, I would struggle to explain the actual plot of the film, but I recall specific scenes from it on the daily. The diary scene. Max von Sydow on a cliff (you’ll know it when you see it). That incredible, phantasmagoric final sequence. It’s a shame the film fails to say anything worthwhile.

10. The Passion of Anna (1969)

For a director known for slow, contemplative films, The Passion of Anna is surprisingly fast-paced. The film rarely takes time to reflect on the morally questionable actions of its characters, instead continually introducing new plot points and intriguing mysteries. Of course, that’s not to say that the film is shallow - it’s a rumination on infidelity, violence, and loss, and it handles these themes competently. But the focus is never on preaching a message to the audience as it is in other Bergman films. Instead, the film gives more room for the plot to take center stage, which is quite a refreshing approach in this filmography. While certainly not Bergman’s most essential film, The Passion of Anna is certainly worth a watch. Did I mention the film looks ridiculously gorgeous, too?

9. Cries and Whispers (1972)

Cries and Whispers might be Bergman’s best looking film. I mean, just look at that shot above. Most of the movie is enveloped in blood crimson drapes and carpets, with only the stark white clothes of the protagonists providing any contrast. Perhaps more than any other entry in his filmography, Cries and Whispers acts primarily as a stunning showcase of production design and acting prowess (this is arguably Harriet Andersson’s best performance, rivaled only by Through a Glass Darkly). The plot takes a backseat to Bergman and co. showing off what they can accomplish through a simple story about a dying woman and her visiting sisters. It’s a breathtaking film, though it falls just short of greatness due to its lack of a meaningful thematic grounding.

The Great

8. Wild Strawberries (1957)

Wild Strawberries is a testament to Bergman’s monumental insight into the human condition. The fact that he was able to make such a moving, grounded film about mortality and the acceptance of impending death at the age of 39, extraordinarily early into his career, is astounding. But Wild Strawberries is that and so much more. In his final performance, Victor Sjostrom portrays an elderly professor going on a road trip to receive an honorary degree. Along the way, he encounters a variety of hitchhikers who cause him to reflect on his life and ultimately come to terms with his past regrets. On the surface level, the film is perfect. It’s well composed, formally precise, and extremely well acted. The story is touching and relevant to any audience. The only thing that prevents Wild Strawberries from ranking higher on this list is that it feels so distant. The technical perfection of the film prevents the viewer from approaching it on a visceral level. It’s an emotional story that can only be accessed intellectually, and that keeps it from being truly transcendental.

7. Through a Glass Darkly (1961)

This is an interesting one. 75% of Through a Glass Darkly is textbook Bergman - solemn Swedes isolated on an island, staring off into the distance and being passive aggressive to each other, blah blah blah. But the final 20 minutes of this film may be the most engrossing sequence Bergman ever captured. From the moment Karin and Minus enter the shipwreck to the moment the credits roll, everything happening on screen is unbelievably haunting. I don’t want to get into specifics out of fear of spoiling the brilliance of the ending, but suffice it to say, I don’t think I will ever forget the ending of Through a Glass Darkly. Unfortunately, while the rest of the film is certainly competent, it’s boilerplate Bergman and fails to accomplish anything. It almost feels as if this would work better as a short film, with the first hour being condensed to thirty minutes. Regardless, it’s absolutely worth trudging through the first hour of this film to reach the incredible ending.

6. Autumn Sonata (1978)

From here on out, these films are more or less required viewing. Autumn Sonata is Ingmar Bergman’s one and only collaboration with Ingrid Bergman (unrelated, as far as I’m aware), who delivers one of the finest performances in all of cinema as a world-class pianist visiting her estranged daughter, played by Liv Ullmann. The focus of this film really comes down to the acting. Autumn Sonata is a chamber film in the purest sense of the term, with the majority of the narrative taking place within a single room and featuring dialogue between only two characters. The plot, too, is very simple. The entire 90 minutes revolves around mother and daughter attempting to resolve the tensions that have plagued their nearly non-existent relationship for years. Ullmann and Bergman deliver breath-taking performances that are virtually unrivaled in their emotional range and ability to evoke complex feelings through facial expressions. Though the story is not the most complex in Bergman’s catalog, Autumn Sonata is worth viewing again and again solely for its beautiful and pained acting.

5. Scenes from a Marriage (1973)

Scenes from a Marriage is another interesting entry in Bergman’s catalog in that it puts the majority of the focus on one aspect of film: this time, it’s dialogue (as opposed to production design in Cries and Whispers, acting in Autumn Sonata, etc.). The first of Bergman’s two lengthy mini-series, Scenes from a Marriage is a masterclass in crafting real, impactful relationships through dialogue. Everything else in this film takes a backseat to allowing Bergman to flex his writing chops through the great performances of Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann. One of the few Bergman films to deliver an explicit message to the audience, Scenes from a Marriage is a moving meditation on what it means to be a good partner and how love manifests in the real world.

4. Fanny and Alexander (1984)

Fanny and Alexander is one of the coziest films I’ve ever seen. The other Bergman mini-series, the plot of this one is quite similar to Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter - after the death of their father, two children are pulled away from their idealistic life by a manipulative and abusive step-father supposedly motivated by religion. Though where Laughton’s film struggles with tonal consistency, Fanny and Alexander is exquisitely crafted and perfectly straddles the border between childhood and adolescence as the titular Alexander (Bertil Guve) grows up under the watchful eye of Bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjo). The latter acts of the film bring in elements of magical realism and low fantasy that elevate the film to mythical proportions, turning a relatively simple narrative into an epic coming-of-age saga.

The Masterpieces

3. Persona (1966)

Yeah, I get the Bergman hype. This is simply a fantastic film. Well, maybe that’s not a good way to put it - Persona is anything but simple. From its narrative to its editing, performances to cinematography, this film revels in complexity, inviting the viewer to form their own interpretation of the nightmarish imagery on screen. There’s no “message” delivered to the audience here. Sure, there are thematic suggestions perhaps encouraging one to consider concepts of duality, identity, mental illness, and the relationship between artist and subject, but Persona is subjective if nothing else. That’s the greatest strength of the film. I’m typically someone who enjoys a film that has something to say and says it well (hence my top two), but Persona is a masterclass in crafting a singular work of art that refuses to explain itself. If nothing else, I have to respect it for that - luckily, the film is also wildly enjoyable and has left a lasting impression on me as well.

2. The Seventh Seal (1957)

The canonical favorite Bergman film, The Seventh Seal does everything right. There’s not a line in this film wasted, a shot meaningless, or a performance phoned in. Every member of the cast and crew is firing on all cylinders to craft this haunting and moving tale of mortality. There are so many memorable sequences in this film, from the opening on the beach and the church scene to the closing shot of the hill burned into the mind of anyone who’s seen The Seventh Seal. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the film is its personification of Death, with Bengt Ekerot turning in a genuinely chilling performance. Choosing to portray Death as an actual being is a risky one, as it could quickly turn to campy indulgence, but Ekerot does a fantastic job of making the character truly menacing. The Seventh Seal is Bergman at his very best, and it would be number one were it not for feeling slightly distant from the viewer.

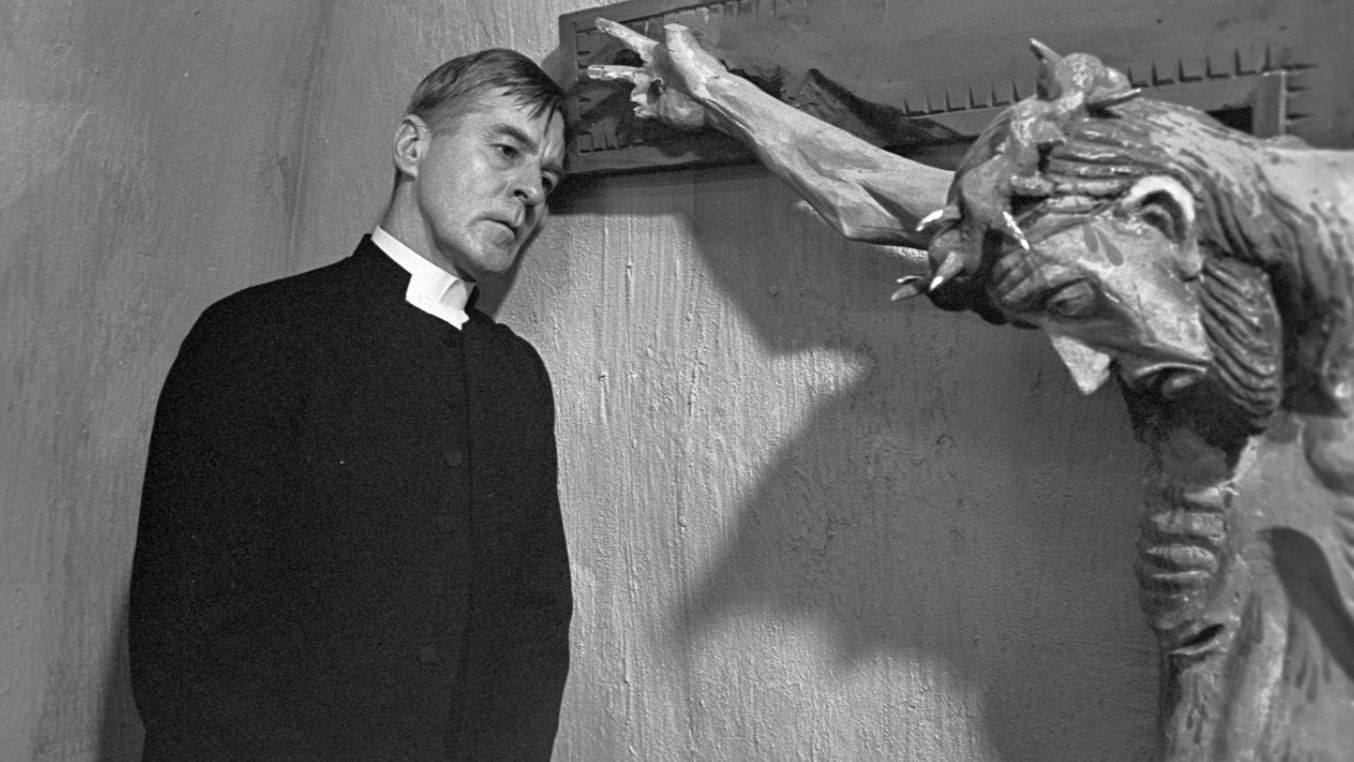

1. Winter Light (1963)

Winter Light is a film that I truly believe everyone needs to watch. Despite being released over sixty years ago, its themes are arguably even more relevant today than they were in 1963. As I’ve said before, I enjoy films that speak to the audience and deliver a message to them, and Winter Light does that more artfully than perhaps any other film I’ve seen. Starring Gunnar Bjornstrand as Tomas Ericsson, a disillusioned preacher attempting to figure out how to move forward in his profession as he loses faith, this film feels like Bergman’s most intimate and personal, even to the point of emotional claustrophobia. We see every step of Pastor Tomas’s pain, his sorrow, and his ultimate decision to keep living and preaching out of responsibility and the need to do something delivered through a masterful script that highly inspired Paul Schrader’s recent film, First Reformed. Winter Light is a perfect film. I highly recommend you go see this film soon, as the world disenchants us more each and every day.

Popular Reviews