Don’t hate the player, hate the game: Netflix’s breakout hit Squid Game

Squid Game has taken the recipe for a bingeable Netflix show and seasoned it to perfection. The Korean drama follows Seong Gi-hun, a father who has gambled with both his life and his relationship with his young daughter. With little left to lose and everything to gain, he enters to compete in a series of children’s games, along with 455 other debt-ridden and desperate contestants, enticed by a handsome cash prize. The twist? Losing gets you killed.

The premise feels like an episode of Black Mirror — both shows examine how far from humanity we might stray in a twisted reality — but where the British anthology sometimes gets lost in its own absurdity and pessimism, Squid Game never loses its focus and heart. Through a wholly entertaining (and bloody) narrative, creator, writer, and director Hwang Dong-hyuk scrutinizes the rampant wealth inequality of South Korea and its ramifications on individual autonomy. With impressive pacing, characters you’ll root for, viral elements, and strong underlying social commentary, Squid Game establishes itself as one of Netflix's best releases.

When we first meet Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), blowing his daughter’s birthday gift money on horse betting, I felt we were meant to judge him. While there’s a huge tonal shift between the first sequences and the remainder of the show, I do think the disjunction works here. Initially, Gi-hun is bumbling and a bit clownish, and it’s sobering to watch Lee’s acting become more serious as the series progresses and as Gi-hun faces his own mortality. And when he reveals his traumatic backstory (based on a real-life labor strike), we’re forced to reckon with our own unfair initial judgement of Gi-hun. I began the series saying, ‘Really, this guy?’, and by the end, I was heralding Gi-hun as a moral champion and commendable protagonist. That’s a testament to Hwang’s patient hand in developing his characters.

The other contestants are equally as compelling, including Gi-hun’s logical foil Sang-woo, stoic Sae-byeok, and eccentric Han Mi-nyeo. They take a spectrum of approaches to the game: cunning and cruelty, generosity and teamwork, and pure chaos. I appreciate that Hwang isn’t afraid to kill off his main players, often by pitting them against each other, which keeps Squid Game always unpredictable.

Like Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite (2019), Squid Game serves as vehement criticism of South Korea’s wealth inequality and modern capitalism. Hwang presents us with several contradictions: gambling is a detriment for the poor but ripe entertainment for the rich (and the rich profit off the pain of the poor); contestants play the game to survive, while a certain contestant plays for nostalgic fun; the workers repeat, “We are not here to hurt you, we are here to give you a chance,” and massacre dozens of contestants in the next breath.

Episode 2, where contestants are allowed to leave the game on a majority vote, is arguably the most boring of the series (certainly the least action-packed), but might be the most important for Hwang’s message. Contestants are given the illusion of choice, but, quickly reminded of the desperation of their real lives, nearly all find they have no choice but to return and compete. The episode is aptly titled “Hell”; Hwang assigns the label of “Hell” not to the horrific, deadly game, but to the real lives of South Korea’s indebted. The contestants have no real control over their own lives — the Front Man even explains that most are terminally ill or have signed away their rights to loan sharks.

Hwang posits the impossibility of autonomy in a plutocracy through clever storytelling, furthering his point through subplots including one in which a few game workers harvest contestants’ organs to sell on the black market as a side hustle. He’s so successful in his messaging that North Korean propaganda is even pushing Squid Game as evidence of South Korea’s flawed capitalist model.

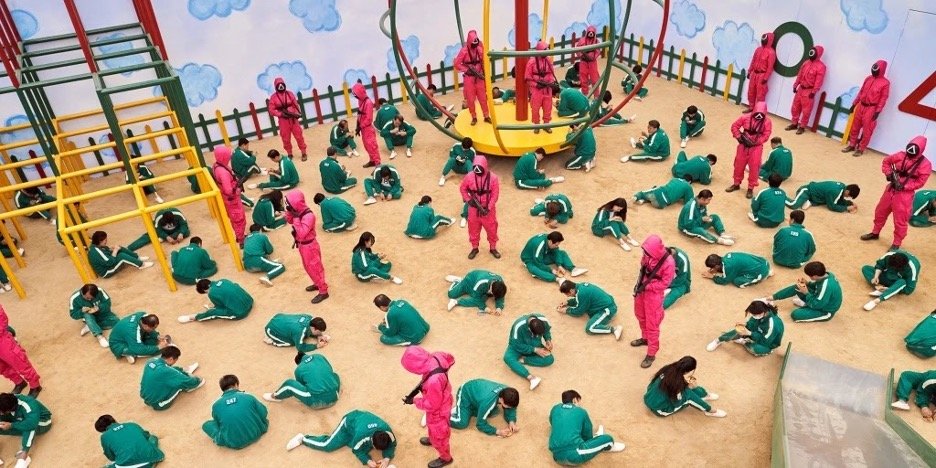

Beyond his knack for meaningful storytelling, Hwang’s eye for detail makes Squid Game an aesthetically stunning experience. He deals in muted colors filming in Seoul, juxtaposing these against the unnaturally vibrant teals and reds of the game facility. The whole set is nightmare fuel, invoking childhood innocence and flipping it on its head. From the sand playground to the coffins shaped like gift boxes, each set piece and prop feels meticulously designed to contribute to Hwang’s sadistic vision.

The games themselves are imaginative and so well executed, and not just for show. Hwang uses them as a tool to thrust his characters into gripping moral dilemmas. My favorite game was the bridge, where contestants hop on a checkerboard of tempered and ordinary glass panels suspended in the air. Guess wrong, and they fall to certain death but clear a path for those behind them regardless. It’s a (very unethical) case study in morality: the contestants’ fates are all tied, and it’s up to them to decide who takes the next uncertain jump. I held my breath the entire episode. Also worthy of mention is Red Light, Green Light, during which Hwang kills over half his characters in the first episode. The slaughter is one of most disturbing endings to a pilot I’ve ever seen, but man is it good TV.

Besides being a thrill to watch, Squid Game has become quite the phenomenon to engage with. The show has spawned a massive fan community on TikTok: the Red Light, Green Light call quickly became the platform’s most popular sound, and a Dalgona candy challenge mimicking episode 3’s game has gone viral. My friends and I send fan videos back and forth that point out details and foreshadowing easily lost on first watch, and I love confirming my own fan theories by browsing through comment sections.

Engaging as a fan has never been more accessible, and I’m excited to see how Squid Game’s uniquely casual and extensive fan base changes how we interact with media. If the show’s own merits aren’t enough to convince you to watch, let the fear of missing out on the online dialogue compel you. Because trust me, by skipping Netflix’s most enthralling, sharp, bloody, and downright entertaining release, you truly are missing out.

Squid Game is now streaming on Netflix.

More Articles by Hayley Sussman

Popular Reviews