Richard Linklater’s Big Year: Nouvelle Vague and Blue Moon

After catching Blue Moon at the Philadelphia Film Festival with her, I had a cheesesteak lunch with my sister (hers was vegetarian). I asked her what she would ideally like to see made into a “Richard Linklater movie.” Even between his ardent champions and detractors, there is little disagreement about Linklater’s style. He is the eminent voice in “movies about nothing.”

My sister, for her part, didn’t quite know what would make the perfect Linklater project for her tastes. I struggled with the question, too. This is because his movies are frequently revelatory. They seem to simply spring from pure happenstance, yet you are left feeling as though they were always meant to be. That is the director’s gift, I think: to make cinema effortless.

This year, Linklater opened and closed the festival season with two films: Blue Moon, which hit stateside cinemas this past weekend, and Nouvelle Vague (to be released theatrically on Halloween and then streaming on Netflix, the film’s US distributor, by the middle of next month). Though radically different formally and thematically, both films freeze exquisite moments in time—evoking more than just texture and sound, but a feeling of living in a time and place divorced very much from our own.

Blue Moon is set in Sadi’s bar in 1943. It follows Lorenz Hart (Ethan Hawke), the original lyricist for Richard Rogers, on the opening night of Oklahoma!—the first show Rogers wrote with his future collaborator and de facto replacement for Hart, Oscar Hammerstein. As others have been quick to opine, Ethan Hawke is totally unrecognizable. Physically, he is shrunk to a little over five feet (the real Larrry Hart was a very small man) by use of oversized props, trick perspective, and a clever wardrobe. He’s given an atomic combover and Hawke stretches his syllables, creating a unique lilt that almost completely sonically disguises him. More than impersonation, though, Hawke embodies Hart’s acerbic wit, his profound sadness, and his awkward manner. He is more than a tortured artist; he is an elder statesman of the musical theater, ruined equally by the jingoism and aw-shucks honesty he sees in the modern theater and his doomed love of a twenty-year-old Yale girl.

But despite its rich central performance, Blue Moon struggles to develop under its self-imposed formal limitations: sequences are artificially elongated, moments are beaten from ambiguity and dramatic weight, and the plotting smacks of misplaced tautology. Hawke shuffles in and out of rooms and staircases and on and off bar stools (though more frequently on them—perhaps to help with the illusion of his diminutive stature), but the blocking is uninspired, even amateur. As such, the geography of the space never comes to bear in heightening the tension or drama. The best single-set films will leverage their limited setting, but Blue Moon rarely does.

Crucially though, Linklater does not overstay his welcome. Blue Moon concludes at a brisk one hundred minutes, without scarcely a wasted moment. Certainly, the script repeats itself, but the actors find new ways to mine the material. Andrew Scott plays a contemptible yet sensible Rogers and Margaret Qualley succeeds in sharpening a character who would be nearly depthless otherwise. Really, Blue Moon is at its best when recreating the feeling of the war-time Theater District, more than in illuminating Lorenz Hart. Linklater’s romantic images mask the sadness of the protagonist, rightfully perhaps. Hart himself would probably agree that the show ought to go on.

I was lucky enough to see the premier of Nouvelle Vague at the Cannes Film Festival. The film received one of the longest ovations of the festival—perhaps not a surprise considering that Nouvelle Vague is about the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s landmark film Breathless and takes place (in part) in the city of Cannes during the late 1950s. Nouvelle Vague (down to its untranslated title; it does, indeed, mean “New Wave”) is exceedingly French. But Linklater still lends it his signature homespun American incredulity.

Unlike Blue Moon, Nouvelle Vague is endlessly energetic, even restless. In this regard, Linklater meaningfully replicates the devil-may-care pluck of the French New Wave—a film movement known for its freshness and loose, often ad-libbed style. I see the DNA of Linklater’s own efforts in Breathless, which explains the director’s evident passion for the material. In particular, despite mimicking Godard so uncannily, actor Guillaume Marbeck seems a match for Linklater himself, too.

The attention to detail in the film cannot be underrated. Linklater and team poured over dozens of hours of behind-the-scenes footage from Breathless; the director and his cinematographer even spent time arguing about the identity of an object Jean Seberg puts in her mouth at a café between shots. Eventually, they determined it was a sugar cube. And sure enough, Zoey Deutch’s Seberg chews a sugar cube in the film.

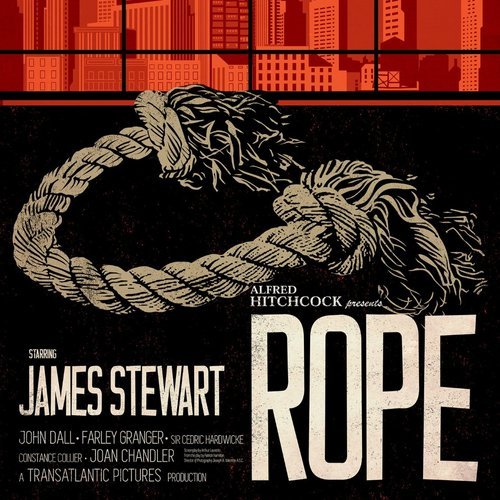

Even the camera is precisely the same model that Godard used to shoot his film (the Arriflex 35mm). The grainy, black-and-white image is part of what makes Nouvelle Vague so intimate and real. It helps, too, with the immersion that practically every sequence has easter-eggs for cinephiles: Truffaut, Varda, Rossellini, and others all pop their heads in the frame—something like a film fanatic’s equivalent of The Avengers.

I briefly spoke with Mr. Linklater on the day following the premier and he related to me his own reservations about making a film as self-referential as Nouvelle Vague. He cautioned me—a film student at the very beginning of my journey—to wait a while before making a movie about moviemaking. It is Linklater’s rebuke of pretension that has endeared me to this newest effort. His passion for film history and filmmaking decorates every frame. And it’s rather contagious.

That is why I am calling 2025 Richard Linklater’s Big Year. With these films, he tackles big subjects, though notably without betraying his quiet, naturalistic sensibilities. Nouvelle Vague is easily my preference of the two, but I think both films admirably depict the history they are built on. Blue Moon is a portrait of the theater and Nouvelle Vague of the cinema. One is honest and stilted, as if put on a stage, and the other is graceful and yearning and romantic. To answer my own question, I think this year has proven that there is no perfect Linklater subject. He is capable of finding the joy in everything.

Popular Reviews