Beneath the Skin: Black Swan 15 Years Later

15 years ago today, Daren Aronofsky’s psychological thriller Black Swan hit theaters for the first time. The film was seen as a return to form for the director, bringing back much of the neurotic style that his infamous 2000 film Requiem for a Dream had–now dressed in the suffocating clothes of ballet instead of drug induced paranoia. In the time between these two films, Aronofsky released the oddball sci-fi film The Fountain (2006) to mixed reviews, and the quiet and candid The Wrestler (2008) to slightly better reception. Both of these films were a stark departure from Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream and Aronofsky’s affinity for reveling in his audience's misery. Now 15 years since its release, Black Swan has seen continued life in the misguided discourses of social media comment sections. Before I critique these discourses however, I would like to critically discuss the film detached from its legacy and reception.

Black Swan follows a young ballerina, Nina, as the pressure to perfect her part as Swan Queen in Swan Lake corrupts her mind and transforms her body. As the movie progresses, Nina’s psyche begins to fracture into contradictory scenes where the audience cannot tell what is real and what is delusion. Aronofsky intentionally confuses the audience, or rather, forces them to experience Nina’s life as she does.

Similar to the aforementioned Requiem for a Dream, Black Swan is not shy about its body horror. The film has a particular brand of body horror which is hyperfixated on the hands and skin. In one particularly wince-worthy moment, Nina discovers a hangnail on her finger while washing her hands at a party. She picks and peels at it until it is an open wound all the way up the length of her finger. Wait a second, is this a movie about OCD? Handwashing, finger picking, and the impossible obsession with perfection—Aronofsky is certainly alluding to this being the case. Afterall, physical compulsions are characteristically linked to rituals involving the hands and skin, and Nina canonically has a skin scratching disorder. The camerawork is obsessive in its own right, and underscores how Aronofsky wants us to read Nina. Compositions are filled by claustrophobic shots of Nina’s skin. Sets are often designed to generate compounding reflections which multiply Nina’s image into collages of human skin as Nina herself anxiously obsesses over her own body’s image.

Moreover, the film’s obfuscation of reality represents Nina’s intrusive thoughts playing out literally. The hangnail moment I mentioned earlier is revealed to be “all in her head” after she is startled back to reality by a stranger knocking at the door. In another scene, an intoxicated Nina hooks up with Lily–a character meant to be Nina’s foil and “rival” in the film. When Nina confronts Lily the day after, Lily has no recollection of the encounter and laughs at Nina for fantasizing about her. In my reading of this scene, Nina had a non-real intrusive thought about sleeping with Lily. Afterall, intrusive thoughts often take the flavor of sexual acts done onto someone who you aren’t attracted to or are even adversaries with. The alternate reading of this scene is that Nina and Lily did sleep with each other, and Lily was bluffing to sabotage Nina’s role as the Swan Queen. Of course either reading is equally plausible, and I think that is exactly what Aronofsky is going for.

During the climax, Nina discovers Lily in her dressing room also dressed as Swan Queen. Paranoid that Lily is out to sabotage her, Nina kills Lily with a shard of broken mirror. In a later scene, Lily’s body was missing and Nina herself had a wound where she had stabbed Lily. This scene, more directly than any other in the movie, frames Nina’s conflict with Lily as actually being an inward conflict with herself: Nina’s own self-sabotaging anxiety manifested in a living character. It is only when Nina kills this part of herself that she fully transforms into the perfect Swan Queen.

To this end, my reading of Black Swan is predicated on its discussion of the skin: it is a costume that Nina wears for the dysmorphic culture of ballet and it becomes an entity that Nina’s mind turns against as she picks, peels, and washes. Aronofsky is intentionally ambiguous with the events of the movie and never allows the audience to see beneath Black Swan’s skin.

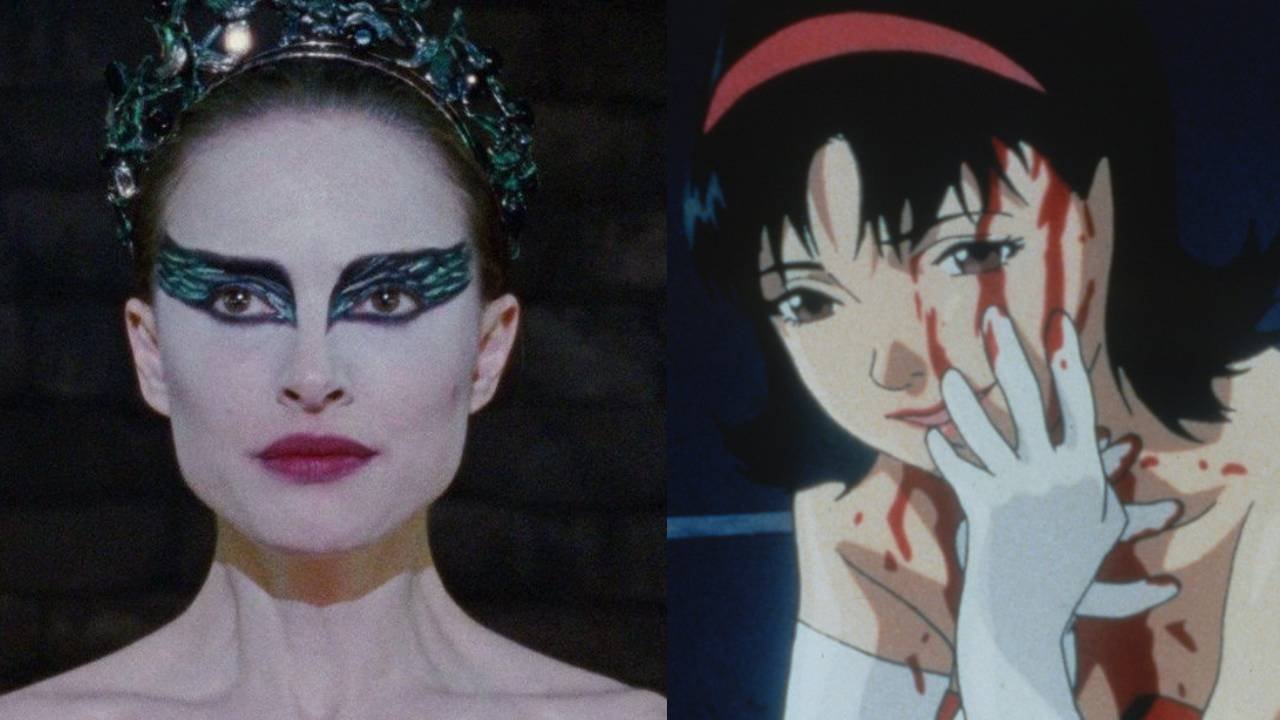

As promised earlier, I also intend to critique discourses around Black Swan, specifically allegations that it is a “rip-off” of Satoshi Kon’s anime film Perfect Blue. Admittedly, the two movies are superficially alike: a story of a young performer who becomes a tool of the industry that eventually devolves into psychological scenes where reality and delusion blur. However, when thinking more critically about the two movies, it becomes obvious that they obfuscate reality in two totally different ways. Black Swan, as mentioned above, blurs reality in order to situate the audience in the same kind of mental state as Nina. Perfect Blue on the other hand, blurs ‘movie sets’ with reality (and at times movie sets within movie sets within reality) to critique the industry. Black Swan is a purely inward conflict where Nina struggles with her own mind turning against itself, whereas Perfect Blue’s conflict is entirely external where Mima’s stardom forces her into perpetual fantasy. As an aside, Requiem for a Dream also catches “Perfect Blue rip-off” allegations on the basis of a scene which Aronofsky partially recreated. Haven’t people heard of an homage? One could say that Aronofsky is obsessed with Perfect Blue.

A more compelling comparison in my opinion would be the horror classic Carrie (1976). Both Black Swan and Carrie are twisted coming of age films. In Black Swan, Nina is pulled in opposite directions of purity and corruption by her mother Erica and her dance company’s director, Thomas, respectively. Likewise, Carrie is pulled in opposite directions of purity and corruption by her mother Margaret and her P.E teacher Sue, respectively. Both movies climax with a performance scene (the dance of the black swan in Swan Lake, and Carrie taking the stage as prom Queen). In these moments, both Nina and Carrie become “corrupted” completely. I especially love to compare the bedrooms of Nina and Carrie as both are styled to the taste of a young child rather than a teenager.

Whether or not you believe that Black Swan is ripping off Perfect Blue, Carrie, or some other film is not the point of this discussion. Rather, it is obvious that movies which accurately represent obsessive and compulsive tendencies or obsessive compulsive disorder such as Black Swan are largely misunderstood and have a distinct gap in their discourses when it comes to their OCD representation. To this end, here is my contribution to the discourse: Black Swan phenomenally illustrates the tribulations of obsessive compulsive disorder, and in such a way that forces the audience to live with OCD for a not-so-short 109 minutes. Aronofsky accomplished an insurmountable task for many directors by depicting OCD in such a nuanced and thrilling way which never insisted that it was even a story about OCD to begin with.

Popular Reviews